FLASHPOINT: The Final RMD Regulations – The High Points

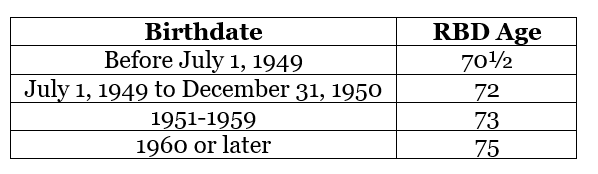

By S. Derrin Watson, Esq. Alison took the easy job. She wrote about the 36 pages of proposed RMD regulations. And she asked, ever so sweetly, if I would write about the 260 pages of final regulations that were issued at the same time [Treas. Reg. 1.401(a)(9)-1 through -9, “Final Regs”]. I thanked her. I love this stuff. Complicated RMD rules? Bring it on! (That’s one reason “we’re your ERISA solution!” We have people with different skill sets, so we can bring the right person to the job at hand.) The good news is that the Final Regs did not make major changes to the 2022 proposed regulations. But there are important refinements and clarifications, and, of course, discussion of many of the SECURE 2.0 RMD changes that Congress passed after the Treasury released the proposed regulations. However, certain SECURE 2.0 changes are in the proposed regulations that Alison discussed, and the two sets of documents are intended to be read together. This article will highlight some of the most important changes. Applicability Date The Final Regs are applicable beginning with the 2025 calendar year. For years before 2025, practitioners are to follow the 2002 regulations, with good faith interpretations of the SECURE Act and SECURE 2.0 changes. If a plan follows the 2022 proposed regulations, that represents a good faith interpretation of the SECURE Act rules. Required Beginning Date It used to be so simple. The Required Beginning Date (“RBD”) was April 1 of the calendar year following the year the participant turned 70½ (or retired, in the case of a participant other than a more than 5% owner). The SECURE Act and SECURE 2.0 both changed the age. The final and proposed regulations make it clear that the RBD (outside of the retirement exception) is based on the when the participant was born, as shown below: The preamble to the Final Regs notes that some practitioners prefer the old simplicity. They asked if they could go back to 70½ for everyone. The Treasury correctly observed that a plan certainly can provide for mandatory distributions at age 70½ (to the extent consistent with Code §411(a)(11)), but that does not make those distributions RMDs or make the RBD earlier than April 1 of the year following the year the participant attains the RBD Age. As a result, payments before the first distribution calendar year as determined under the law are not subject to the distribution rules that apply to RMDs. Therefore, they are eligible rollover distributions, subject to 20% mandatory withholding; RMDs are not. Roth Accounts and RMDs Thanks to SECURE 2.0, a participant’s designated Roth account is not considered in determining the participant’s RMD during the participant’s lifetime. The first year the Roth account is considered is the year following the year in which the participant died. For example, December 31, 2023, Jack has a $200,000 pretax account, a $29,000 after-tax contribution account, and a $50,000 Roth account. Jack turns 77 in 2024, and his distribution factor under the Uniform Life Table (“ULT,” used for determining lifetime RMDs) is 22.9. His RMD is $229,000/22.9, or $10,000. The Roth account is disregarded. Suppose Jack dies in 2025. His 2025 RMD is calculated without regard to the Roth account, whether the RMD is paid to Jack while he is alive or is paid to his beneficiary after he dies. The 2026 RMD, however, the first RMD calculated using the age of the beneficiary and using the single life table (SLT) rather than the ULT, includes the Roth balance. There are two other points about the Roth account: Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDB) Once the participant dies, the amount and timing of RMDs in a defined contribution plan will depend on three things: The SECURE Act added the EDB classification. The post-SECURE rules permit an EDB generally to stretch RMDs over a longer period than other beneficiaries, if they choose to do so. EDBs include the surviving spouse, minor children of the participant, disabled and chronically ill individuals, and individuals who are not more than 10 years younger than the participant. The proposed regulations defined minor children as those who had not attained age 21 when the participant died. The Final Regs retain that definition but add that a beneficiary is a “child” of the participant if the beneficiary is the participant’s child, stepchild, adopted child, or eligible foster child under Code §152(f)(1). The proposed regulations required that a health care professional certify that a beneficiary was disabled or chronically ill when the participant died. That certification must be provided no later than October 31 of the year following the year of death. Because of the delay in issuing the Final Regs, the documentation requirement can also be satisfied if the documentation is provided by October 31, 2025. The preamble notes that the certification need not be overly detailed. Distributions Don’t Stop Without a doubt, the most controversial part of the proposed regulations related to a rule that applied to participants who died after the RBD and had an ODB as beneficiary. The regulations provided that the beneficiary would receive life expectancy RMDs (computed using the SLT) beginning in the calendar year following the year of the participant’s death, and that the entire defined contribution account must be distributed no later than December 31 of the year containing the 10th anniversary of the participant’s death. (The RMD for the year of death might have gone to the participant before he or she died; if it did not, it should be paid to the beneficiary, but the amount should be determined as it would have been had the participant been alive.) For example, suppose Portia died at age 75 in 2022, leaving her 401(k) account to her son, Bob. Portia died after her RBD and the 2022 RMD must be paid to Bob if it wasn’t paid to her before her death. Beginning in 2023, Bob must start taking RMDs based on his age and the SLT. Suppose Bob turned 50 in 2023. The SLT factor is 36.2 and so the 2023 RMD would be the December 31, 2022, account balance, divided by 36.2. For 2024, the divisor decreases by 1.0 to 35.2. No later than December 31, 2032, the plan must distribute the entire account to Bob. Some people read the law and certain IRS publications to say that Bob didn’t need to take annual RMDs, but that he could wait and withdraw the entire account in 2034. While that would be true if Portia had died before her RBD, once she reached her RBD, annual distributions are mandatory. The IRS has issued a series of Notices that provided that neither the plan nor the beneficiary would be penalized for not making annual distributions in a situation such as Bob’s for 2021-2024. So, if Bob didn’t take the 2023 or 2024 RMDs, he is not subject to the now 25% penalty tax. But he must start taking annual RMDs in 2025. In doing so, he will not need to “make up” the earlier years. The 2025 RMD is the December 31, 2024, account balance divided by 34.2. Bob must still withdraw the entire account by December 31, 2032. Other Mandatory Payouts There are other mandatory 10-year payouts under the Final Regs: The 2022 proposed regulations included another mandatory payout, which was limited to situations in which a participant died after the RBD and left the account to a designated beneficiary who was older than the participant. The Final Regs removed that rule. Spouse as Participant SECURE 2.0 added a rule that applies if a deceased participant’s sole beneficiary was the surviving spouse and the spouse takes RMDs using the life expectancy rule. There are three advantageous provisions that are uniquely available to surviving spouses: Rules 2 and 3 have been in the law for years, and the Final Regs say they apply without regard to whether the first rule, allowing the spouse to use the ULT, is elected. The new proposed regulations, as Alison pointed out, say that the first rule is automatic if the participant dies before the RBD. Otherwise, while the choice to use the ULT is subject to spousal election, the plan can provide it as a default. If the participant dies on or after the RBD, and the election applies, distributions to the spouse are based on the greater of the ULT factor for the spouse, or the SLT factor for the deceased participant. The latter approach of using the participant’s SLT could be useful if the participant was substantially younger than the spouse. There were two surprises in the new proposed regulations on this point that are worth reiterating here: Separate Share Rule with Trusts While a see-through trust can be treated as a designated beneficiary (or, to be more precise, the beneficiaries of the trust are treated as the beneficiaries of the plan), it hasn’t been possible to use the separate share rule with those beneficiaries.

Example (without trust). Peter dies in 2020 at age 74, leaving his 401(k) account to his five siblings, ages 65 to 79. Before December 31, 2021, the account is divided into five separate accounts, one for each sibling. The 65-year-old uses her age to compute RMDs and the 79-year-old uses his age (and so has faster RMDs). Example (with trust). Assume the same facts as the prior example, except Peter leaves the account to a see-through trust for the 5 siblings. The trust is treated as a single designated beneficiary and uses the life expectancy of the oldest of the five siblings. The separate share rule has not been available.

Under the Final Regs, the trust can use the separate share rule if it qualifies as an immediately divided trust. Upon the participant’s death, the immediately divided trust is split into subtrusts and is thereupon terminated. The main trust and the subtrusts must all be see-through trusts. There can be no discretion as to how the participant’s balance will be allocated to the subtrusts after death. In this case, each subtrust (and its beneficiaries) are treated as separate from the other subtrusts, just as though the separate share rule applied. Under the 2022 proposed regulations, this rule was limited to situations in which a disabled or chronically ill beneficiary was involved. It is now available regardless of the health of the beneficiaries. As Alison pointed out, under the new proposed regulations, this technique works even if a beneficiary receives immediate distribution after the death of the participant, rather than having his or her interest held in trust. Reduced Penalty Tax The Code imposes an excise (penalty) tax on failure to timely distribute an RMD. For failures after 2022, the tax rate is 25% of the undistributed amount. However, SECURE 2.0 allows the participant or beneficiary to reduce the tax to 10% if the participant takes the distribution from the appropriate plan during a “correction window” and files Form 5529 with the IRS reflecting the 10% tax. Under the Final Regs, the correction window begins on the date on which the RMD should have been made and was not (i.e., December 31 of the RMD year), and ends on the last day of the second tax year that begins after that date (or, if earlier, the date the IRS mails a formal deficiency notice or actually assesses the tax). For example, if a participant should have taken an RMD in 2024, the participant can pay the reduced penalty tax by taking the distribution any time before the end of 2026 and filing the Form 5329 paying the reduced tax. The RMD must be taken from the plan that should have distributed the amount. But if the participant could have chosen the plan or account which pays the RMD (such as one of several IRAs, or one of several 403(b) plans), then any of those plans or accounts can pay the corrected amount. Updated Eligible Rollover Distribution Regulations Treas. Reg. §1.402(c)-2 defines eligible rollover distributions. That regulation had not been updated in more than 20 years. The RMD regulations include a complete update and rewrite of this important regulation to reflect various statutory changes, as well as the final RMD regulations. The preamble to the regulations clarifies that, if a nonspouse beneficiary chooses to receive a distribution from a plan, rather than requesting a direct rollover to an IRA, it is treated as an eligible rollover distribution subject to mandatory 20% income tax withholding. The new rules add a detailed regulation for the situation in which a surviving spouse of a participant who dies before the RBD uses the 10-year rule to avoid annual RMDs from the plan, but then rolls the money to the spouse’s IRA, from which the spouse will use the life expectancy rule. Effectively, the regulations force the spouse to “catch-up” on the missed annual RMDs, by treating that amount as not being an eligible rollover distribution. Much, Much More These are just the highlights. There are important clarifications, changes to defined benefit and annuity rules, rules on qualified longevity annuity contracts, trust and estate planning rules, and more. For a more detailed (and lengthy) discussion, subscribers can consult my RMD chapter appearing in the Qualified Plan eSource, the 403(b) Plan eSource, or the Plan Distribution eSource, each of which is published by ERISApedia. And, of course, if you have questions, please call us. After all, we are your ERISA solution!

- Posted by Ferenczy Benefits Law Center

- On September 26, 2024