FlashPoint – The New Fiduciary Regs: A Practical Review – Part I

Okay, here is the FBLC take on the new DOL fiduciary regulations. As in the past with prior proposals, we have broken our response into different parts. Today’s information will look to give just some broad rules and structure of the Regulation, itself, which defines what makes someone an advice fiduciary and what that means.

Part II will discuss the Best Interest Contract Exemption, or BICE, as it is being called (albeit the pronunciation is somewhat in the air. Some practitioners say, “Bic” like the pen; others say “Bice,” to rhyme with “mice.” We’ll see which option prevails nationally. I vote for “Bice.”) This is the part of the package under which someone who is a fiduciary is able to avoid the self-dealing rules of the prohibited transaction structure, even though he or she is getting uneven compensation.

Part III will try to parse what is going on in the industry and what people are saying and give you some perspective on any remaining pitfalls or concerns that should make you lose sleep or take actions other than what you initially thought were acceptable.

Our goal here is to provide you with concise, understandable information. We will leave it to others to write pages and pages of detailed discussion of specific minutiae that might affect one or two of their clients. If we do not address something that concerns you in these pages, please call us, and we will be happy to get into any specifics you require. But, here, we want to provide the broadest group of our readers with what we think that they likely need to know.

Introduction

The new Regulation Package—which contains both a regulatory interpretation of ERISA’s definition of who is an advice fiduciary, as well as certain exemptions from the prohibited transaction rules to permit those advisors to get paid in a manner consistent with the investment industry—does not attempt to redefine who is a fiduciary. In fact, it pays homage to the actual language of the law, providing that, if you give advice and get paid for it, you are a fiduciary.

What the Regulation does do is to clarify what constitutes “fiduciary advice.” The DOL then endeavors, as requested by the overwhelming amount of testimony and comment letters it received over the last several months, to provide fiduciary advisors with a structure under which they may be paid in a “customary” manner—i.e., flat fees and certain variable fees. This part occurs through prohibited transaction exemptions, most particularly the BICE.

Please note from the outset that ERISA Section 3(21) defines three types of fiduciaries—those that have or exercise discretion as to the management of the plan; those that have or exercise discretion as to the investment of plan assets; and those who give investment advice for a fee or other compensation. The new rules relate solely to this third category of fiduciary, and do not touch the other two. So, if you are a Plan Administrator under ERISA or a trustee, for example, your role in the plan operations is not being changed by these rules. Your advisors need to be concerned about those changes.

Step 1: Are You Giving Advice?

Whereas you might think that the first inquiry would be whether you are a fiduciary, it is important to note that, with these rules, the type of advice provided defines the fiduciary. Therefore, the first question really is: are you doing what you need to be doing to be a fiduciary under these rules?

Under the Regulation, you are providing investment advice if you:

Provide to a plan, plan fiduciary, plan participant or beneficiary, IRA, or IRA owner, a recommendation regarding:

- The advisability of acquiring, holding, disposing of, or exchanging securities or other investment property;

- how to invest the securities or other investment property once they have been rolled over, transferred, or distributed from the plan or IRA;

- the management of securities or other investment property, including:

- investment policies or strategies;

- portfolio composition;

- selection of other persons to provide investment advice or management;

- selection of investment account arrangements (such as brokerage vs. advisory);

- rollovers, transfers, distributions from a plan or IRA, including amount or form of such action.

What Is a Recommendation?

Note the specific language of the rules. You must make a recommendation to be giving advice. The DOL defines a recommendation to be:

A communication that, based on its content, context, and presentation would reasonably be viewed as a suggestion that the advice recipient engage in or refrain from taking a particular course of action.

The analysis of whether something is a recommendation is objective, according to the DOL. So, the issue is not whether you thought or your client thought you were making a recommendation. The issue is whether it seems like a recommendation to a reasonable individual.

The Regulation and its preamble spend considerable time identifying fine-line differences between what is or what is not a recommendation. When all is said and done, and all the parsing of language is complete, it appears that a recommendation is one that would reasonably be an encouragement to act. Therefore, generalized suggestions without enough specific detail for someone to follow your lead should not be a recommendation.

What Is Clearly Not a Recommendation?

FBLC (as well as Suze Orman and numerous other people with newsletters or TV broadcasts) is relieved to note that generalized suggestions to the public that are not targeted to a given individual are not recommendations.

Simply offering a platform (or suggesting a certain platform), giving a list of available investments that meet criteria outlined by the client, or providing samples of investment alternatives in response to a request, are not recommendations.

Education about investments or the plan is not a recommendation. While the Regulation ostensibly overrides IB 96-1, the long-existing guidance on what represents education vs. advice, the net result is not much different. Telling someone about the plan or about investment information in general (e.g., investment concepts, historic differences in rates of return, effects of fees and expenses and inflation, and the like) is not advice.

An employee doing his or her job with regard to the plan, such as a committee member who suggests to the others on the committee that they consider whether a specific investment ought to be added to the plan portfolio, is not giving investment advice. But, be careful. An individual who happens to be an employee would be considered to give advice if that is, in fact, what he/she is doing. So, for example an employee whose job includes giving investment advice to his/her coworkers is an advisor. Similarly, an employee who happens to be a licensed broker on the side, might be a fiduciary if he/she gives recommendations to his/her coworkers to invest in a certain way. In other words, don’t get too cute.

There is a change from the proposal in relation to asset allocation models that do not represent a recommendation. Under the proposal, you could show a model but you couldn’t identify any actual investments in your model (if you did, it was considered to be a recommendation of those investments). Under the final rules, you can use and identify the designated investment alternatives (DIAs) that are offered under the plan in your models, and you won’t be considered to be giving advice, if: the models are based on generally accepted investment theories; all material facts and assumptions used in the models are disclosed; the models are accompanied by a statement that the participants should consider their other assets, income, and investments in addition to their plan or IRA interests when making decisions; and a DIA is used, and the models are accompanied by an identification of all other DIAs with similar risk and return characteristics, and a statement about where information about those other DIAs can be obtained.

Are there gray areas remaining? Certainly. But, those are for another day.

Step 2: Are You a Fiduciary Vis-à-Vis That Advice?

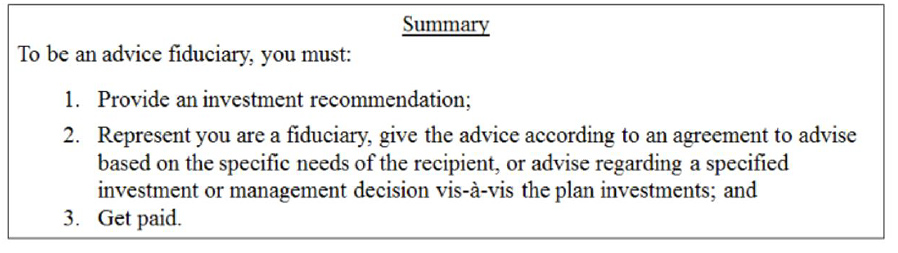

If you give advice of the type discussed above, you are a fiduciary if you:

- Represent or acknowledge that you are a fiduciary;

- Render the advice pursuant to a written or verbal agreement, arrangement, or understanding that the advice is based on the recipient’s particular investment needs; or

- Direct the advice to a specific recipient regarding the advisability of a particular investment or management decision with respect to securities or other investment property of a plan or IRA.

There is one more requirement for you to be a fiduciary: you must get paid in some manner for the advice, either directly or indirectly.

It does not appear that you need to admit you are an investment fiduciary—saying you are a fiduciary is enough to meet the first bullet point, if you are giving investment recommendations. The DOL makes it clear that it will not let someone call him-or herself a fiduciary, give investment advice like a fiduciary, and try to parse the title to the client’s disadvantage. If you are a fiduciary and you don’t want to be responsible for your investment advice, don’t give investment advice.

Step 3: I’m a Big Shot Fiduciary, Too, Exception

Notwithstanding the information above, you will not be considered a fiduciary advisor if you are giving your advice to someone who should know better than to believe that you are impartial.

Basically, this rule applies if the plan fiduciary (i.e., the advice recipient) is:

- A bank

- An insurance carrier

- An investment advisor under the Investment Advisors Act of 1940 and is registered as such under the state

- A broker-dealer

- An independent fiduciary that holds or manages at least $50 million of assets.

There are other hoops through which everyone must jump. The important part of this exemption is that it doesn’t apply to a normal plan fiduciary or IRA holder. It just applies to the big kids who do this for a living.

Step 4: Okay, I’m a Fiduciary. So What?

Once you are found to have given the right kind of advice and received payment for it, you need to follow the rules for being a fiduciary. The Regulation and the prohibited transaction exemptions then provide means for a fiduciary to provide services and get paid the way advisors normally get paid.

If you are a fiduciary, you owe duties to the plan and its participants: loyalty (i.e., to act for the exclusive benefit of the participants and beneficiaries, and to provide for plan benefits and defray plan expenses); prudence (like a prudent person who knows what he/she is doing would do); and to follow the plan document and ERISA.

If you don’t, the plan participants can sue you, both for losses and lost profits, as well as to force you to disgorge your presumably ill-gotten gains. Furthermore, if you are a fiduciary, you are subject to the self-dealing prohibited transaction (PT) rules, which are found in both ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code (the Code). Under these rules, if you engage in a transaction in relation to the plan for which you receive some personal financial benefit (or if you are somehow adverse to the plan), you are engaging in a PT. This means that you must reverse the transaction, making the plan whole, and you are liable for excise taxes.

It is these PT rules through which the DOL is reaching advisors to IRAs. IRAs are subject to the PT rules that are in the Code, which are substantially the same as those in ERISA. Furthermore, through the operations of the federal government, the DOL has been given regulatory oversight over both the ERISA and the Code rules on this topic. So, even though the DOL is not really in the business of regulating things that have nothing to do with the employment relationship, it can indirectly regulate IRA advisors through this delegated authority. In reality, whether the IRS has any resources available to enforce any of these new regulations is a whole other discussion.

If you are engaging in an activity that would violate the PT rules, you can only continue to do so if there is an exemption from those rules. Enter the BICE. This is the way that people who get compensation that does not, on its face, comply with the self-dealing prohibitions, will nonetheless be able to continue to do business in the retirement plan space.

For that, you need to see Part II of this series. More to come.

- Posted by Ilene Ferenczy

- On April 18, 2016